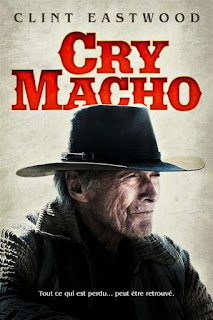

Cry Macho

Starring Clint Eastwood, Dwight Yoakam

Directed by Clint Eastwood

Before I get into some criticism of Clint Eastwood’s new movie, Cry Macho, I do want to say that I like what he’s doing these last fifteen years or so, especially when he’s old enough to contentedly retire. Instead, he’s taking the Woody Allen route: putting out relatively low-budget movies, which he (and Warner Brothers) know won’t be blockbusters (his last was Million Dollar Baby) but which will make back well more than what they cost. And I’d much rather see movies like this, with all their flaws, than most huge-budget action movies full of CGI effects and monsters and robots. For the cost of one Transformers movie, you could make one hundred of these.

That said, a lot of Cry Macho is surprisingly badly done, most significantly the acting by Eastwood and (who should be listed as co-star) Eduardo Minett. Also country star Dwight Yoakam, but we’ll give him a pass. Eastwood of course has never had much of a range, but he’s always used it well. Here though, he’s just too old for the character he’s playing, and all his (and most everybody’s) dialogue falls flat. That, and/or many of the supporting characters, like most all of who appear here as mexicans are over-acting. Given that the screenplay is also a little wooden, and maybe the editing is off (some scenes seem like the should be cut short by just a second, right when someone is done speaking, without the small silences, which are not profound, nor any kind of cowboy western irony. If anything, some of the scenes in Mexico look and sound like the cheap Mexican action movies churned out down there, and not in an ironic way.

Mike Milo (Eastwood) an old down-on-his-luck ranch hand, is asked by his boss, Howard Polk (Yoakam) to go down to Mexico to bring back Polk’s long lost son Rafo (Minett), who he had with a rich mexican woman, Leta (Fernanda Urrejola). Milo feels obliged, since Polk saved his life after Milo broke his back and ruined his rodeo-circuit life by an addiction to painkillers.

Eastwood is 92 (!) and looks it. I haven’t read the book from which this movie is based, but Mike Milo feels like he should be maybe 50, tops. It gets almost ridiculous when Milo interacts with his love-interest, Marta (Natalia Traven) who seems about a reasonable 50. In fact, Traven is the best actor in the movie: every time Marta appears, there is warmth, and she seems to bring out better acting in both Eastwood and Minett.

I wondered if Cry Macho would go dark à la Cormac McCarthy (the movie takes place in 1980, the same year as No Country For Old Men, and the nascent cross-border drug trade does make a small appearance) and although there is some minor violence, it never quite gets that bad. What it does have is Eastwood’s old-school Republican values (which are common in most westerns of any time period) in which a young man is failed by his parents and saved and ‘made into a man’ by an older male mentor (see also for example Gran Torino), who instills an american capitalist work ethic (there are numerous shots of Milo and Rafo getting paid for doing work in the movie). And even when Milo realizes that Polk has not been entirely honest with him, he still claims to Rafo that Polk (remember that he’s Milo’s boss) is a good man.

I love that Eastwood is still making movies. I just wish that, like Allen, he would finally step aside and just direct. On the other hand, the crowd in the theatre in Vernal, Utah, ranch country where I saw Cry Macho—who were all mostly older than I—came to see him. He’s such an iconic actor that I too feel that, like, Go Eastwood! Go down to Mexico! Kick some ass and fall in love with a mexican señorita with a heart of gold! But these are also old-school Republican generalizations. McCarthy falls into this too: in Mexico there are either good people or bad people, and you can almost hear the echo of a George W. speech.

And yet, and yet, like in McCarthy’s Border Trilogy books, we feel the tug of wanting the good people from both countries to make connections, to find some kind of common ground in the Border Country. This is embodied in Rafo: half-mexican half-americano, fluent in spanish and english, clinging to his idea of “macho” or machismo as a form of bravery, even though it’s a form of pride, and seems to get him nothing but pain.

Milo has a sense of pride too, though centered in a work ethic. It’s an honor code, which annoys the rich people he meets on both borders, but endears him to the working class. Which is why I ultimately liked the movie, because even if Eastwood values the ‘working’ part of working class, he still recognizes that is a story about class. Milo’s place is not among the rich, and he’s more content for it. He’s modeling, or trying to model, this for Rafo, and the question of the movie is whether Rafo will realize this.

No comments:

Post a Comment